Industry and construction statistics – short-term indicators

This article examines recent statistics in relation to developments for both industry and construction in the European Union (EU). Short-term business statistics (STS) are provided in the form of indices that allow the most rapid assessment of the economic climate within industry and construction (as well as services), providing a first evaluation of recent developments for a range of economic activities. STS show developments over time, and so may be used to calculate rates of change, typically showing comparisons with the month or quarter before, or the same period of the previous year. As such, STS do not provide information on the level of activity, such as the monetary value of output (value added or turnover) or actual prices.

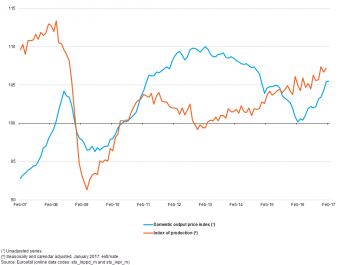

Figure 1: Production and domestic output price indices for industry (excluding construction), EU-28, 2007–2017

(2010 = 100)

Source: Eurostat (sts_inppd_m) and (sts_inpr_m)

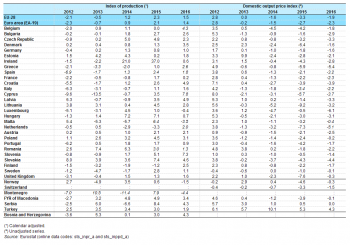

Table 1: Annual growth rates for industry (excluding construction), 2012–2016

(%)

Source: Eurostat (sts_inpr_a) and (sts_inppd_a)

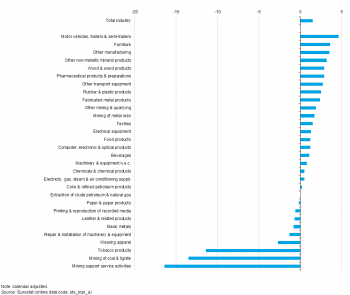

Figure 2: Annual growth rate for the industrial index of production, EU-28, 2016

(%)

Source: Eurostat (sts_inpr_a)

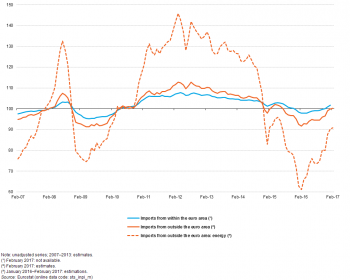

Figure 3: Industrial import price index, euro area (EA-19), 2007–2017

(2010 = 100)

Source: Eurostat (sts_inpi_m)

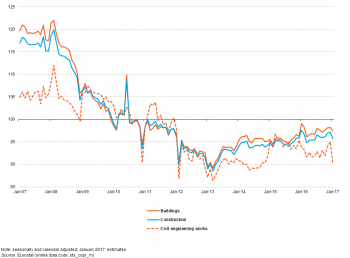

Figure 4: Index of production, construction, EU-28, 2007–2017

(2010 = 100)

Source: Eurostat (sts_copr_m)

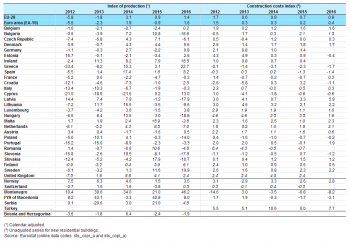

Table 2: Annual growth rates for construction, 2012–2016

(%)

Source: Eurostat (sts_copr_a) and (sts_copi_a)

Contents

[hide]

Main statistical findings

Industry

The impact of the global financial and economic crisis on the EU-28’s industrial economy and the muted recovery can be clearly seen in two of the main industrial indicators, namely the industrial production index and the index for industrial domestic output prices. Over several years there was relatively stable output and price growth across the EU-28, which was interrupted by the onset of the crisis in May 2008 (see Figure 1), when the month-on-month rate of change for the EU-28’s industrial production index turned negative, while the index for domestic output prices peaked two months later in July 2008. The rapid fall in industrial output lasted one year, returning to a positive rate of change in May 2009, while domestic output prices reached their lowest level in July 2009 and experienced a run of relatively sustained increases from October 2009.

The decline in industrial output in the EU-28 from its relative peak in April 2008 was particularly steep (-19.5 %), as the relative trough recorded in April 2009 was the lowest level of output since September 1997. By contrast, although industrial output prices in July 2009 were 7.6 % lower than at their relative peak a year earlier, they remained in line with the price levels recorded between October and November 2007 prior to the financial and economic crisis; in part, price developments continued to reflect the relatively high price of crude oil and associated energy-related and intermediate products.

Incomplete recovery and subsequent inconsistent developments

Industrial output in the EU-28 recovered during a period of slightly more than two years from its relative low in April 2009, recording positive month-on-month rates of change for 19 out of the next 28 months through to a peak in August 2011: this peak was 13.9 % above the April 2009 low but nevertheless production remained 8.3 % below its pre-crisis peak of April 2008. Thereafter, there was a gradual decline in EU-28 industrial output observed through until November 2012 during which time output contracted by 4.6 %; subsequently industrial output grew at a relatively slow pace to March 2015, increasing 5.0 % over the course of two years and four months. Between March 2015 and July 2016, the overall development in the industrial production index was irregular, with no sustained period of expansion or contraction. From July 2016 through to January 2017 (the latest data available at the time of writing) the EU-28 index of industrial production increased, up 2.6 %.

By contrast, the return to positive rates of change for EU-28 industrial output prices in August 2009 heralded a more sustained and longer period of price increases. The industrial output price index passed its pre-crisis peak in February 2011 and continued an almost unbroken climb until April 2012 when it stood some 13.6 % above the low recorded during the crisis and 5.0 % above the pre-crisis peak (nearly four years earlier). From April 2012 onwards, the development of industrial output prices in the EU-28 followed an irregular pattern with almost no overall change in prices through to the autumn of 2013. Thereafter, industrial output prices fell at a relatively modest pace during a period of more than one year, reaching a low in January 2015. During the first half of 2015 industrial output prices were relatively stable but fell during the second half of the year and into the first few months of 2016. The most recent data available show a return to increasing industrial output prices, with prices rising at a relatively rapid pace, up by 5.3 % between February 2016 and February 2017.

Recent developments in the EU Member States and various industrial activities

The recovery in industrial activity across the EU from mid-2009 onwards was less widespread and regular than had been the preceding downturn. Whereas every EU Member State recorded lower output in 2009 than in 2008, three Member States — Greece, Croatia and Cyprus — recorded further reductions in 2010 while all of the remaining Member States recorded an increase. In 2011, the same three Member States again recorded a fall in their industrial output and they were joined by Ireland, Spain, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal and the United Kingdom. By 2012, most of the Member States (once again) reported a negative rate of change for industrial output, the exceptions being the three Baltic Member States, Denmark, Austria, Poland, Romania and Slovakia (see Table 1), while the situation in Malta reversed, as it too recorded an increase in industrial activity.

Developments for 2013 were mixed, as 15 of the 28 EU Member States recorded a contraction in industrial output and the level of production across the whole of the EU-28 fell by 0.5 %. The largest declines in activity were recorded in Cyprus, Malta, Sweden, Greece, Finland, Italy and Luxembourg, where industrial production fell by at least 3.0 % between 2012 and 2013. In 2014, a majority of Member States — 19 in total — reported an increase in output (compared with a year before), most notably Ireland where the industrial production index increased by 21.0 %. By contrast, Malta reported a decrease of 5.7 % and falls of 2.0 % or more were also reported by the Netherlands and Greece. In 2015, Ireland again reported exceptional growth due to on-shoring activities of some large multinational enterprises, with industrial output up 37.0 %; the next largest increases were reported by Slovakia (7.4 %) and Hungary (7.1 %). Only two of the Member States reported a decline in industrial production in 2015: -1.2 % in Finland and -3.3 % in the Netherlands. In 2015, Greece reported an increase of 1.0 % in industrial output and Cyprus an increase of 3.5 %, their first annual increases since 2006 and 2008 respectively. Developments for 2016 were quite similar to those observed during 2015, in that only two Member States — Luxembourg and Malta — reported falls in industrial output, -0.4 % and -3.5 % respectively. Ireland’s run of extremely large increases came to an end as it posted an increase of 0.6 %. Both Cyprus and Greece confirmed their returns to positive rates of change, with stronger growth in 2016 than in 2015, while Finland and the Netherlands reported growth in their industrial output after four and two years of contraction respectively.

Equally, the downturn in activity during the financial and economic crisis was spread across almost the full range of industrial activities: in 2009, there was just one industrial activity (at the NACE Rev. 2 division level) that reported continued growth within the EU-28, as the output of pharmaceutical products and preparations rose by 3.1 % compared with the year before. The recovery in 2010 was also relatively widespread: there were nine exceptions (among the 30 NACE Rev. 2 divisions covered by the index), where output continued to contract in 2010. The number of activities that recorded a fall in output remained at nine in 2011, with six of the nine activities that had contracted in 2010 continuing their downward path. The inconsistent nature of the recovery was evident in 2012 and 2013, as only six of the 30 NACE Rev. 2 divisions recorded an expansion in output in 2012, while the level of production increased for one in three of the NACE divisions in 2013. In 2014, a more widespread expansion was observed, with again nine divisions reporting a fall in output, among which the manufacture of tobacco products where output fell by 12.1 %. In 2015, the number of activities for which a decline in output was observed rose to 11, among which six had also recorded a decline in 2014. The largest fall in output in 2015 was 9.7 %, again for the manufacture of tobacco products. In 2016, the number of activities for which a decline in output was observed dropped back to nine, among which six had also recorded a decline in 2015 and four a decline every year since the onset of the crisis (2009–2016): coal and lignite mining, tobacco products manufacturing, wearing apparel manufacturing, and printing and reproduction of recorded media. The largest fall in output in 2016 was 16.4 % for mining support service activities, whereas the largest increase was 4.6 % for the manufacture of motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers (see Figure 2).

Import prices

Industrial import prices for the euro area peaked in July 2008, regardless of whether imports were from outside the euro area or from other EU Member States within the euro area (see Figure 3). Thereafter, prices of imports from within the euro area fell over a 10-month period by a total of 7.8 %, whereas the prices of imports from outside the euro area fell by a total of 15.0 % over the same period. From their low point in May 2009, prices for imports from within the euro area increased by 13.1 % through to April 2012, after which they declined 9.2 % through to February 2016 (despite a moderate increase between January and May 2015); in the 11 months through to January 2017 (the latest period available at the time of writing) they increased 4.0 %.

Starting from the same low point in May 2009, import prices from outside the euro area followed a similar development, with an increase of 23.5 % through to August 2012, a decrease of 18.8 % to February 2016 (again with a moderate increase in early 2015), and an increase of 9.5 % over the most recent 12-month period through to February 2017.

Construction

The downturn in activity for construction within the EU-28 lasted longer than for industry. Despite occasional short-lived periods of growth, the index of production for construction fell from a peak in February 2008 to a low in March 2013, a decline that lasted in total five years and one month and left construction output 26.2 % lower than it had been. Construction output expanded by a total of 7.6 % during the next 13 months and between then (April 2014) and the most recent period for which data are available (January 2017) output remained relatively stable (see Figure 4).

The construction of buildings is the dominant part of construction output, and unsurprisingly output for building work shows a similar development to the overall indicator for construction, although the magnitude of the contraction from February 2008 to March 2013 was slightly greater, totalling 26.9 % in the EU-28. For civil engineering the developments were less clear cut: from February to December 2008, civil engineering output in the EU-28 fell in a similar manner to the developments seen for building output. However, there followed a substantial increase in January 2009, mainly due to a large expansion in civil engineering work in Spain. Civil engineering output then followed the broad downward path observed for construction as a whole, also reaching a low point in March 2013, having lost 22.9 % of its value compared with its peak in February 2008.The recovery in activity from this relative low was more muted and short-lived for civil engineering than for buildings, as civil engineering output rose by 5.7 % between March and December 2013. During the first half of 2014 there was a dip in civil engineering activity (down 2.8 %), followed by a more substantial recovery (9.1 %). This in turn was followed by a further decline between March 2015 and January 2017 (the most recent period for which data are available), equal to 6.9 %, such that in January 2017 the level of civil engineering output in the EU-28 was just 4.3 % above its March 2013 low point.

The long and deep downturn in construction activity was widespread within the EU-28, illustrated by the fact that all but five of the EU Member States — the exceptions being Denmark, Ireland, Spain, Malta and the United Kingdom — experienced at least two years of contraction in construction output during the most recent five-year period (2012–2016) for which data are available, despite the fact that this period excludes the first four years of the downturn associated with the global financial and economic crisis and its aftermath (2008–2011). In 2012, a large majority (22 from 28) of Member States reported a contraction in construction output, contributing to the 5.8 % fall recorded for the EU-28 as a whole (compared with a year before). By 2013, the number of Member States reporting a contraction in activity had fallen to 19 and this decreased to 10 in 2014 when the EU-28 recorded its first annual increase in construction output (3.1 %) since 2007. In 2015 and 2016, 13 of the Member States reported a decrease in construction output and the EU-28’s expansion in activity initially slowed to 0.9 % in 2015 before accelerating to 1.4 % in 2016. Six Member States reported decreases in construction that were greater than 10.0 % in 2016, with the largest falls in Hungary (18.8 %), Latvia (17.9 %), Slovenia (17.8 %) and Bulgaria (16.6 %). By contrast, output rose by 22.7 % in Greece and also by more than 10.0 % in Ireland, Cyprus and Sweden.

During the period 2012–2016 (as shown in Table 2), Italy and Portugal each recorded five consecutive negative annual rates of change in their construction activity; indeed, the downturn in activity was even longer in Italy (extending back to 2008), while in Portugal the last positive annual rate of change was recorded in 2001. In 2016, Croatia recorded a positive annual rate of change for construction output for the first time since 2008.

By 2016, construction output was less than half the level it had been prior to the crisis (in 2007) in Cyprus (-55.4 %), Slovenia (-58.3 %), Portugal (-59.3 %), Ireland (-60.7 %) and Greece (-67.0 %). During the period 2007–2016, construction output declined by more than one fifth in half of the EU Member States, while there were only six Member States — Malta, Finland, Sweden, Germany, Poland and the United Kingdom — where there was higher activity in 2016 than there had been in 2007. Malta recorded by far the largest expansion in construction activity when comparing 2016 with 2007, as its index of production rose by 39.7 %.

Despite the large and sustained contraction in construction output during and following the global financial and economic crisis, construction costs did not fall on an annual basis in the EU-28, although the rate of growth slowed from just over 4 % between 2006 and 2008 to 0.5 % in 2009. Somewhat larger increases in construction costs were reported between 2010 and 2012 (between 1.4 % and 3.0 %), since when increases have been below 1.0 % (see Table 2). In seven EU Member States, construction costs fell in 2016 (and in 2015 in one additional Member State for which 2016 data are not yet available). For Spain, 2016 was the second consecutive year for an annual fall in construction costs, while longer runs of falling costs were observed in Cyprus, Poland (both four years) and Greece (five years). By far the largest increase in construction costs in 2016 was observed in Latvia, as growth of 5.8 % was recorded, more than double the 2.3 % growth recorded in Malta, which was the next largest.

Data sources and availability

Short-term business statistics (STS) are compiled within the scope of Regulation (EC) No 1165/98 of 19 May 1998 concerning short-term statistics. The STS Regulation brought major changes and improvements in the availability and timeliness of indicators following its implementation. The STS Regulation has been amended and adjusted to meet emerging user needs, generally in relation to monetary union and more specifically to the requirements of the European Central Bank (ECB).

Indicators common to industry and construction include the production index and labour input indicators concerning employment, wages and salaries, and hours worked. For industry there are additional STS indicators concerning turnover and output prices, which are compiled as a total and also distinguishing between domestic and non-domestic markets, with a further analysis of non-domestic markets between euro area and non-euro area markets. In a similar manner, there is a distinction made for the data on industrial import prices between imports from euro area and non-euro area markets. For construction activities there is a distinction in the production index between building and civil engineering, while additional indicators are collected on building permits, as well as construction cost and price indices.

The presentation of short-term statistics may take a variety of different forms. Unadjusted (or gross) indices are the basic form of an index. Calendar adjustment takes into account the calendar nature of a given month in order to adjust the index. The number of working days for a given month depends on: the timing of certain public holidays (Easter can fall in March or in April depending on the year); the possible overlap of certain public holidays and non-working days (some fixed holidays can fall on a Sunday); whether or not a year is a leap year, and other reasons. Seasonal adjustment aims, after adjusting for calendar effects, to take into account the impact of known seasonal factors that have been observed in the past. For example, in the case of the production index, annual summer holidays have a negative impact on industrial production.

Depending on the indicator in question, the EU Member States are required to transmit unadjusted or adjusted data to Eurostat. In the case that Member States transmit unadjusted data, then Eurostat calculates the seasonal adjustment. The Member States’ national statistical authorities are responsible for data collection and the calculation of national time series. Eurostat is responsible for the EU and euro area aggregations.

NACE Rev. 2 is the latest version of the statistical classification of economic activities and has been implemented in STS during 2009. This involved not just changing data compilation practices to use NACE Rev. 2 but also recalculating or estimating a time series in NACE Rev. 2, normally back to the year 2000. Simultaneously with the introduction of NACE Rev. 2, a new base year (2005) was adopted for STS indices to reflect better the economic structure; this in turn was replaced during 2013 with the base year of 2010, once again updating the system of weights in order to accommodate changes in the economic structure. The data in this article are therefore presented using NACE Rev. 2 as indices with 2010 = 100 and using weights from 2010 — see the article on the 2010 rebasing exercise for more information.

Context

The profile and use of STS is expanding rapidly, as information flows have become global and the latest news release for an indicator may have significant effects on financial markets, or decisions that are taken by central banks and business leaders. STS are a key resource for those who follow developments in the business cycle, or for those who wish to trace recent developments within a particular industry, construction or service.

Some of the most important STS indicators are a set of principal European economic indicators (PEEIs) that are essential to the ECB for conducting monetary policy within the euro area. Three PEEIs concern industrial short-term business statistics: production, output prices of the domestic market and import prices. A further two PEEIs concern construction short-term business statistics: production and building permits.

See also

Construction

- Construction producer price and construction cost indices overview

- Construction permit index overview

- Construction production (volume) index overview

Industry

- Industrial import price index overview

- Industrial producer price index overview

- Industrial production (volume) index overview

- Industrial turnover index overview

Services

Short-term business statistics

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Methodology of short-term business statistics — associated documents

- Methodology of short-term business statistics — interpretation and guidelines

- Short-term business statistics (ESMS metadata file — sts_esms)